When we discussed the AFIF calls, we emphasized the importance of transportation in emission reduction and how the European Union has launched various legislative initiatives for this sector.

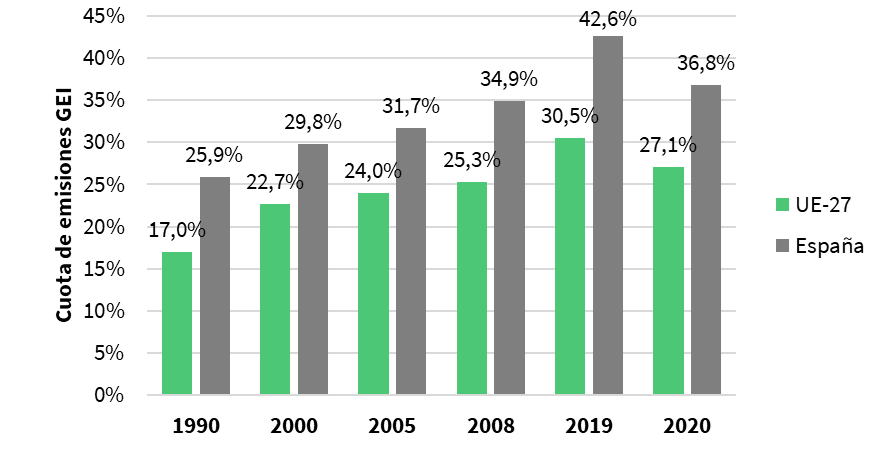

In 2019, the transport sector accounted for 42.6% of greenhouse gas emissions in Spain and 30.5% in Europe (Illustration 1). These emissions will need to be significantly reduced in order to meet the EU’s climate neutrality targets, using the tools set out in the “Fit for 55” package. One of these tools is Regulation (EU) 2023/2405 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 October 2023, known as the “ReFuel EU Aviation” regulation (European Parliament, 2023).

Illustration 1. Evolution of GHG Emissions Share from the Transport Sector

What is the “ReFuel EU Aviation” Regulation?

It is a tool that sets the rules regarding the use and supply of sustainable aviation fuels (SAF), as well as targets for their future use in aircraft. We covered these fuels in detail in the article on Synthetic SAF Production, where we discussed what SAF is and the most common production pathways.

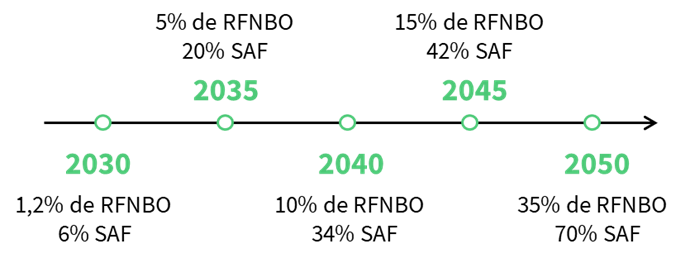

By 2030, 6% of the fuel used in Europe must be SAF, with 1.2% specifically being renewable fuels of non-biological origin (RFNBOs). In this article, we will explore what these percentages mean and how the regulation impacts the aviation industry and the renewable fuel market.

The “ReFuelEU Aviation” Regulation

As mentioned, SAF refers generically to sustainable fuels for aviation. These are alternatives to fossil-based fuels, and within this category, we can distinguish several types:

- Synthetic aviation fuels: SAF that meets the characteristics of RFNBO fuels, meaning it is produced from renewable non-biological hydrogen (electrolytic hydrogen).

- Bio-based aviation fuels: SAF produced from biomass or waste.

- Recycled carbon aviation fuels: Produced from industrial gases containing carbon.

With the distinctions between SAF categories now clear, the regulation also defines the minimum target percentages of SAF supply required from aircraft operators at EU airports. These targets are illustrated in Illustration 2, which also breaks down the minimum percentages that must be RFNBOs.

Illustration 2. Percentage of sustainable aviation fuels at airports over time. Source: (European Parliament, 2023)

It is important to highlight that these targets are subject to a 3% cap on biofuels produced from food crops, due to sustainability concerns.

The regulation also establishes a voluntary labelling system to inform consumers about the environmental impact of flights by route. This label will include the following information:

- The carbon footprint associated with each passenger.

- CO₂ efficiency per kilometre of flight.

- The label’s validity period.

Let’s not forget that, being a regulation, the implementation of ReFuelEU Aviation is immediate and binding across all Member States from the moment it enters into force.

In practical terms, this regulation has succeeded in creating a market for SAF from the very first moment of its implementation, establishing heavy penalties for non-compliance, as we’ll see next.

1.1. Who is affected by the “ReFuelEU Aviation” regulation?

One of the first questions that arises on this topic is who it applies to. Well, this is a regulation focused on commercial aircraft, excluding other types such as military aircraft or those used for rescue missions. However, it is not the airlines that are required to comply with the obligations, but rather the fuel suppliers at airports.

In fact, to enhance transparency, the European Commission recently published a list of airports falling under the scope of application for 2024. The aim is to cover 95% of total traffic originating from EU airports. In Spain’s case, the airports identified are listed in Table 1. These airports must have available the SAF percentages outlined in Illustration 2.

Table 1. Airports subject to the “ReFuelEU Aviation” Regulation in Spain. Source: (European Union, 2024)

| Alicante | Jerez | Reus |

| Asturias | La Coruña | Santander |

| Barcelona | Madrid/Barajas | Santiago |

| Bilbao | Málaga | Sevilla |

| Girona/Costa brava | Menorca | Valencia |

| Granada | Murcia | Vigo |

| Ibiza | Palma de Mallorca | Zaragoza |

And what happens if a supplier does not meet the minimum targets that have been set? In that case, the shortfall with respect to the fixed percentage must be compensated at least in the following period. The first of these will be in early 2025.

The regulation also specifies that the competent authorities (Member States) will be responsible for imposing fines on aircraft operators, airport managers, and aviation fuel suppliers.

1.2. How is it prevented that operators refuel more abroad?

Since sustainable alternative fuels currently involve higher costs, operators might attempt to refuel at airports where prices are lower in order to reduce expenses (Council of the European Union, 2023). For this reason, these operators will be required to refuel at least 90% of their annual needs at the corresponding airports within the European Union.

In the reports that aircraft operators will be required to submit, they must specify everything from the amount used, the airport where it was refueled, to the feedstock used in the conversion process to obtain the fuel. The templates are included in Annex II of the regulation.

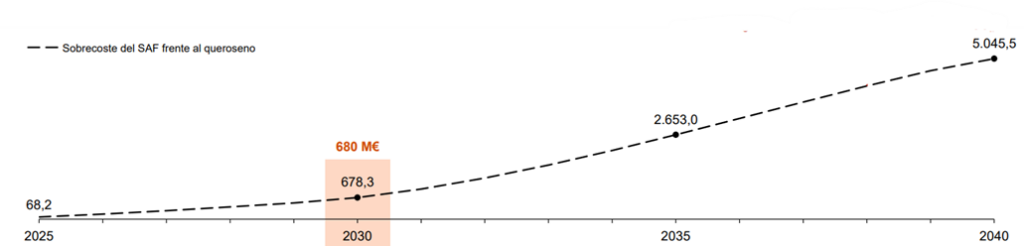

One undeniable outcome of the implementation of this regulation is that the sector’s costs will increase. In Illustration 3, one can see the implication of using the minimum SAF targets set for aviation, showing how the additional cost of using SAF instead of kerosene accumulates. This cost will be influenced by fuel consumption, improvements and reductions in the production costs of these alternatives, and the restrictions associated with greenhouse gas emissions.

Illustration 3. Accumulated SAF Overcost [M€]. Source: (Moeve Global, 2024)

1.3. How does this affect fuel producers?

From the fuel producers’ perspective, it is important to note that they are required to provide information to aircraft operators, allowing them to justify the consumption and the sustainable origin of the fuel. Below is a breakdown of the parameters that must be provided in order to track the renewable character of the fuels:

- Data on the fuel supplier

- Quantity (in tonnes) supplied and the production process used

- Characteristics of the SAF and origin of raw materials

- Life cycle emissions

As a consequence of the consumption obligations shown in Illustration 2, an increase in SAF production is expected. This is why it will be necessary to promote hydrogen production projects and the significant investments they entail. Given its versatility, hydrogen is both a fuel and a product that will also be key in other industries, and the market is already in place thanks to this regulation.

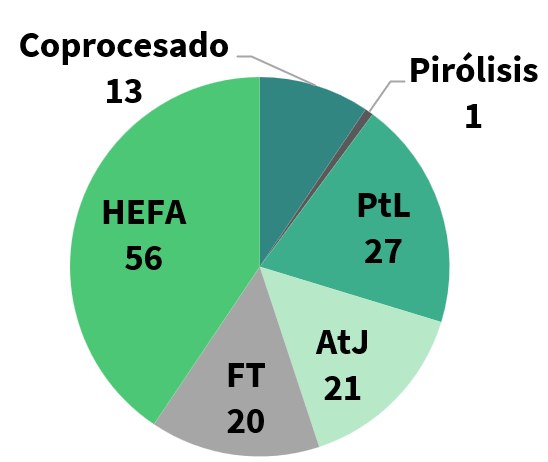

Currently, most SAF plants (both operational and planned) use the hydroprocessed esters and fatty acids (HEFA) technology (Illustration 4), which is based on feedstocks such as fats or vegetable oils. However, the potential of used cooking oils or other raw materials for the production of this type of fuel is limited, making it necessary to advance both the biomass-based production routes (gasification, pyrolysis, alcohol-to-jet) and the synthetic SAF production routes (Fischer-Tropsch and MEOH-to-JET). Although these routes produce bio and synthetic fuels, they share many common links—once synthesis gas is produced, the processes are nearly identical—and their technological development will be beneficial for the synthetic fuels industry. These routes are expected to meet approximately 50% of future SAF demand, making them absolutely essential for the long-awaited decarbonization. At AtlantHy, we are involved in projects using several of these routes, both in pilot and commercial phases.

Illustration 4. Number of operational, under-construction, and planned plants by technology.

2. Case Study

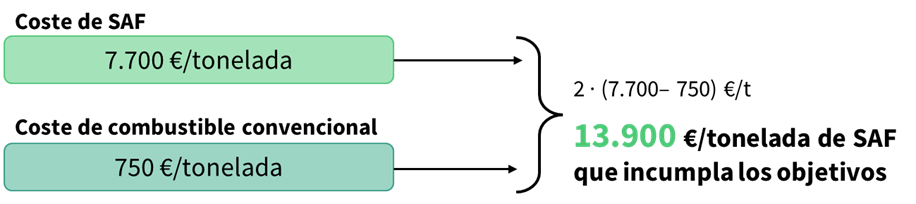

Getting into the subject, the regulation states that Member States must establish a penalty regime for fuel suppliers based on their average SAF content. At a minimum, the fine must be twice the difference in price between SAF and conventional fuel, per tonne and for the amount of fuel that fails to meet the minimum targets.

This will become clearer with an example of how SAF quantity penalties are calculated under the “ReFuel EU Aviation” regulation. We’ve summarized it schematically in Illustration 5, where a supplier would have to face a minimum fine of €13,900 per tonne of fuel until the annual target is met. This is based on the latest reference prices from EASA (European Union Aviation Safety Agency) for 2024, which are around €7,700/t for SAF.

Illustration 5. Example case of calculating penalties for not meeting the 20% minimum SAF target.

2.1. Example Case 1

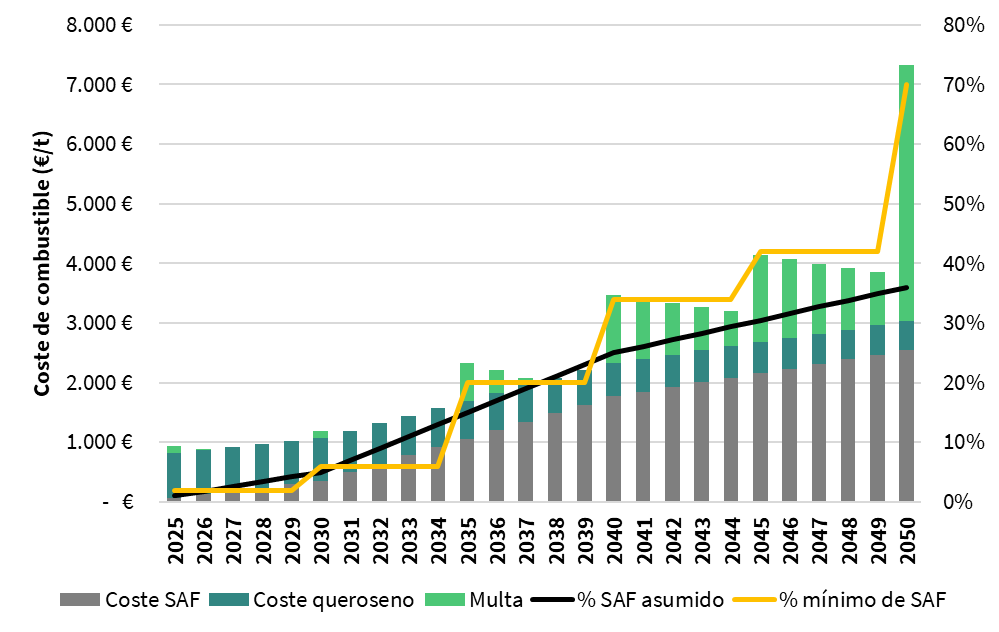

In a scenario where fuel prices remain constant, we have calculated in Illustration 6 the cost that each component would represent in the total, including the penalty for the years in which the EU target is not met.

Illustration 6. Fuel-related costs depending on SAF usage in Case 1.

What we can observe is how, as the targets increase, the total fuel cost—including both the SAF and conventional portions—rises over time.

In this case, we assumed a scenario where the adoption of alternative fuels occurs more gradually than what is required to comply with the regulation. This leads to a larger gap between the amount of SAF consumed and the target in the later years, which is why the penalties become more significant towards the end.

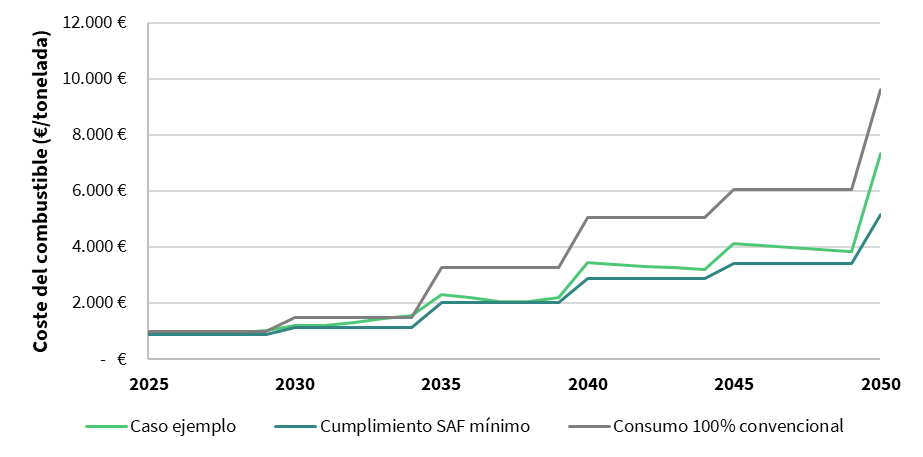

For the same case, in which fuel prices remain constant over time, it is more cost-effective to undertake a sharper transition to avoid penalties—precisely the goal of the regulation. If we now look at Illustration 7, we can see how the difference in the early years is smaller compared to later on, when the cost of meeting the targets is lower than in the previous example. In any case, as we mentioned earlier, costs in both examples will gradually increase with the adoption of a fuel that is currently more expensive than conventional alternatives.

Illustration 7. Fuel cost for Case Example 1 while meeting minimum targets.

Looking at the specific scenario where no SAF is used at all, the result is a much steeper rise in costs compared to the other two examples. In this case, we’re talking about a difference of approximately €2,150 per ton by the year 2040 between using conventional fuels and meeting the SAF consumption targets.

If the costs of these fuels increase or decrease in the future, the scenario will change. Market evolution and technological advancements could lead to lower fuel prices. On the other hand, for kerosene, its future cost will be influenced by the CO₂ emissions fees associated with its use. As a result, SAF may become more competitive than in the baseline example.

2.2. Case Example 2

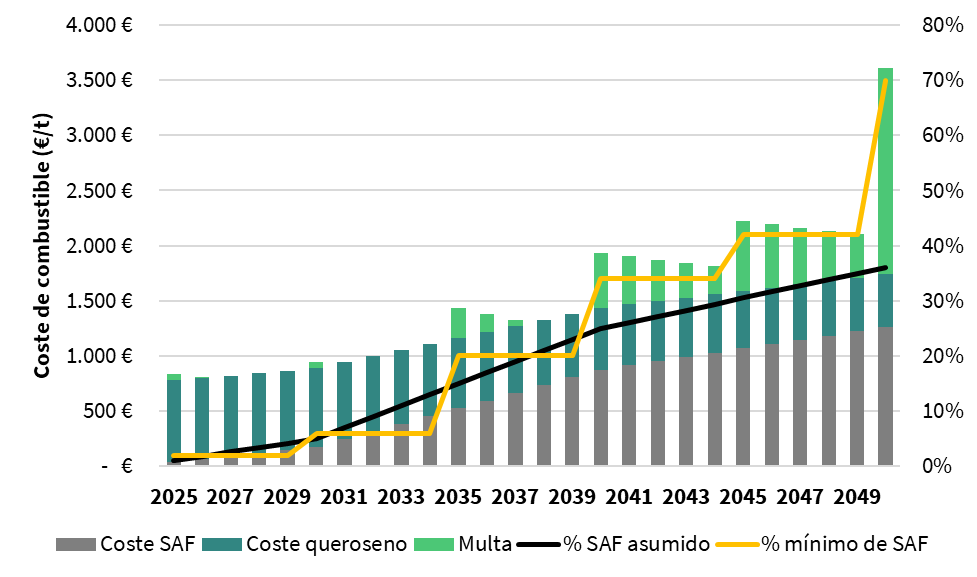

However, in practice, both the production cost and the reference sale price are expected to decrease progressively. As a result, the average fuel price will also tend to drop, mainly due to the lower cost of SAF and the reduction in penalties, as the gap between both alternatives narrows. In this example, the cost of conventional fuel has been kept constant, while the reference price of SAF has been reduced to €3,500 per ton.

Illustration 8. Fuel-related costs based on SAF usage in Case 2

In this second case (Illustration 8), the cost of a penalty at present would be around €5,500, which represents a significantly lower amount compared to the nearly €14,000/ton in the first example. Below, Table 2 provides a comparison between both scenarios to facilitate the analysis. It shows that the proportion of costs associated with compliance obligations increases over time. Likewise, the impact of penalties on the overall fuel cost is relatively smaller, since the required SAF proportions are lower, despite their high price.

Table 2. Benchmark comparison between the two example cases.

| Average cost Case 1 | Average cost Case 2 | Penalty cost Case 1 | Penalty cost Case 2 | |

| 2025 | 940 € | 833 € | 71 € | 35 € |

| 2030 | 1.016 € | 943 € | 297 € | 175 € |

| 2040 | 3.472 € | 1.933 € | 1.770 € | 875 € |

| 2050 | 7.333 € | 3.610 € | 2.549 € | 1.260 € |

In the early years, the selling prices associated with the production costs of sustainable alternatives may be higher, and companies will need to absorb these additional costs. However, this situation is expected to improve as both demand and SAF production increase in the coming years.

3. Conclusions

The “ReFuelEU Aviation” regulation aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and sets specific targets for SAF consumption over the years, as well as for synthetic SAF that meets the characteristics of RFNBO fuels. This means that part of the SAF consumption will need to come from more specific production pathways, which we discussed in the article on synthetic SAF production.

This is an immediate, clear, and quantifiable market signal whose potential cannot yet be met by the projects proposed in Europe through 2030. Both synthetic and biological routes will be necessary, and the scaling up of TRLs for the conversion of raw materials to SAF must be accelerated.

The aviation industry is aware of this urgency (listen to our episode with IAG) and is determined to sign offtake agreements to decarbonize while avoiding the penalties set by ReFuelEU Aviation.

The penalties set by ReFuelEU Aviation are very different from those in other regulations, such as FuelEU Maritime, where using fuels like LNG or paying the fines may be more cost-effective than the sustainable alternative. In this case, decarbonization is the only viable option.

At AtlantHy, we participate in numerous projects related to SAF production, helping companies size their projects, determine production costs, choose the best SAF production pathways, or even apply for grants to achieve greater competitiveness. Would you like us to help you?

4. References

Council of the European Union. (2023). «Objetivo 55»: promover la utilización de combustibles más ecológicos en los sectores marítimo y de la aviación. Retrieved from https://www.consilium.europa.eu/es/infographics/fit-for-55-refueleu-and-fueleu/

European Parliament. (October 31, 2023). Regulation (EU) 2023/2405 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 October 2023 (ReFuelEU Aviation). Retrieved from http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2023/2405/2023-10-31

European Union. (May 24, 2024). List of Union airports in-scope of ReFuelEU Aviation. Retrieved from https://transport.ec.europa.eu/document/download/ce8eae01-435e-4313-8d46-42463c3027ce_en?filename=ReFuelEU_list_airports.pdf

Moeve Global. (September 2024). Cómo hacer de España el líder europeo de SAF. Retrieved from https://www.moeveglobal.com/stfls/corporativo/FICHEROS/Informe-medidasSAF.pdf