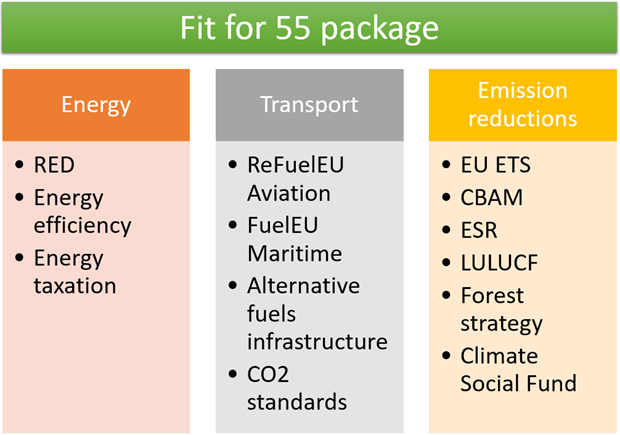

As we discussed in the article on European Plans in the Hydrogen Sector, in order to meet climate targets for emissions reduction, the European Union has developed policies and regulations such as the Fit for 55 package. This package expands the scope of RED II to include key sectors like cement, metallurgy, and chemicals, and sets minimum targets for the use of non-biological origin renewable fuels (RFNBOs) in transport and industry by 2030.

Illustration 1 Policies derived from the Fit for 55 package (Climatalk, 2021)

In this context, specific initiatives have emerged for different modes of transport. In particular, the FuelEU Maritime and ReFuelEU Aviation regulations (integrated within the Fit for 55 package) set limits on the emissions intensity of fuels used in ships and airlines. Their main objective is to promote the adoption of RFNBOs, ensuring that the transition to more sustainable fuels takes place progressively and becomes mandatory.

Thus, ReFuelEU Aviation and FuelEU Maritime not only promote but mandate a minimum consumption of fuels produced from renewable hydrogen, as shown in the following table:

Table 1 Minimum RFNBO consumption percentages, by sector, relative to total consumption by mode of transport (THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, 2023)

| Sector | Minimum consumption rates | ||||

| 2025 | 2030 | 2035 | 2040 | 2050 | |

| Transport | – | 1 % | – | – | – |

| Aviation (ReFuelEU Aviation) | – | 1,2 % | 5 % | 15 % | 35% |

| Maritime (FuelEU Maritime) | – | 1,2 % | 2 % | – | – |

| Industry | – | 42 % | 60 % | – | – |

Among these sectors, maritime transport has a significant environmental impact, accounting for approximately 3% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. To address this challenge, the European Union has developed the FuelEU Maritime regulation, which came into effect on January 1, 2025.

But how will FuelEU Maritime affect shipping companies? What changes will it bring in terms of costs and sector adaptation?

Would you like to know the answers? Stay with us and we’ll explain everything!

Key aspects of FuelEU Maritime

The FuelEU Maritime regulation establishes a regulatory framework to reduce the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions intensity in maritime transport within the European Union. Its main focus is to incentivize the use of renewable and low-emission fuels through a system of progressive obligations and penalties for non-compliance. Below, we outline the most relevant aspects of the regulation:

Scope of Application

The regulation applies to all ships over 5,000 gross tonnage that carry out commercial operations in EU ports, regardless of the flag they sail under. This means that shipping companies from around the world must comply with the regulation if they operate in European waters.

However, certain types of vessels are excluded from the regulation, such as military ships, fishing vessels, and private recreational boats.

Illustration 2 Container Ship

Objectives and Obligations

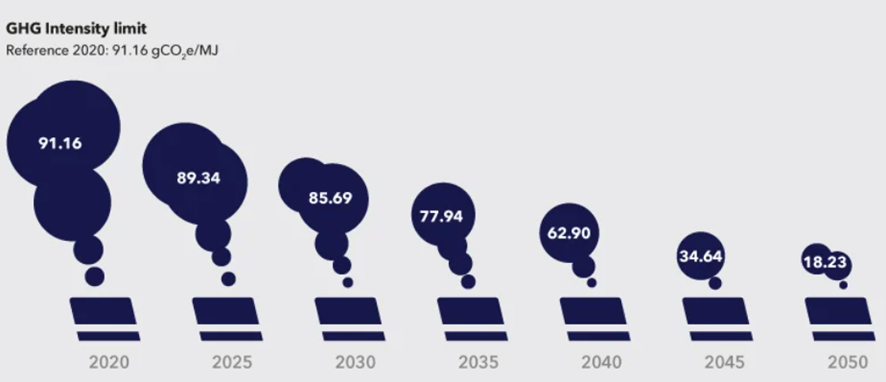

In order to progressively reduce the greenhouse gas (GHG) intensity of the energy used onboard ships operating within the EU, the regulation sets specific GHG reduction targets compared to 2020 levels—starting with a 2% reduction in 2025 and reaching up to 80% by 2050.

Illustration 3 GHG Emission Reduction Percentages Established in the FuelEU Maritime Regulation (DNV, n.d.)

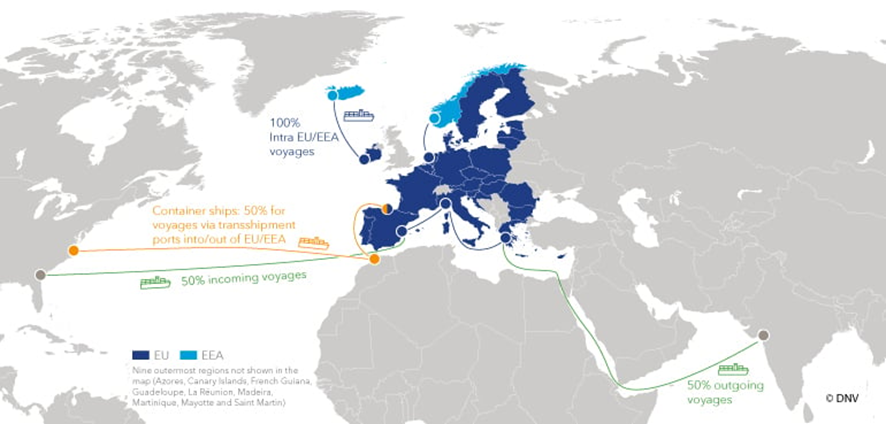

It is important to note that the GHG intensity requirement is applied as follows:

- 100% of the energy used on voyages and during port calls within the EU or EEA.

- 50% of the energy consumed on voyages to or from the EU or EEA.

Illustration 4 Application of GHG Emission Intensity Requirement According to Ship Port Call Type (DNV, n.d.)

The responsibility for complying with the regulation lies with the shipping company, which will be required to replace traditional fuels with more sustainable alternatives such as renewable hydrogen, renewable ammonia, or renewable methanol to meet the established GHG emission reduction targets.

Regarding port calls of passenger and container ships, the regulation also mandates that, starting in 2030, they must use Onshore Power Supply (OPS) in all TEN-T network ports when docked.

As of January 1, 2035, this obligation will extend to all ports equipped with onshore power supply infrastructure.

Also, regarding RFNBO quotas, from January 1, 2034, 2% of the energy used onboard must come from renewable fuels of non-biological origin. This will only apply if the share of RFNBOs in the energy mix for the 2031 reporting period is below 1%. At AtlantHy, we believe this measure is completely insufficient to currently promote the use of RFNBOs in the maritime sector.

Now that we know the objectives and requirements set by the regulation, we can ask: what steps must shipping companies take to meet these goals?

To comply with the FuelEU Maritime regulation, shipping companies must:

- Before August 31, 2024: submit a FuelEU Monitoring Plan to an accredited verifier, describing how the emissions of each vessel will be monitored and reported.

- From January 1, 2025: begin reporting key data on fuel consumption, carbon emissions, and distance traveled.

- By January 31, 2026: individual FuelEU reports must be submitted for each vessel.

- By April 30, 2026: confirm compliance status in the FuelEU Maritime database.

- By June 30, 2026: have the FuelEU Compliance Document available onboard the vessel.

Emission Reduction Calculation Methodology

We’ve discussed that shipping companies must meet emission reduction targets, but how do we calculate a vessel’s emission intensity to determine whether those targets are achieved?

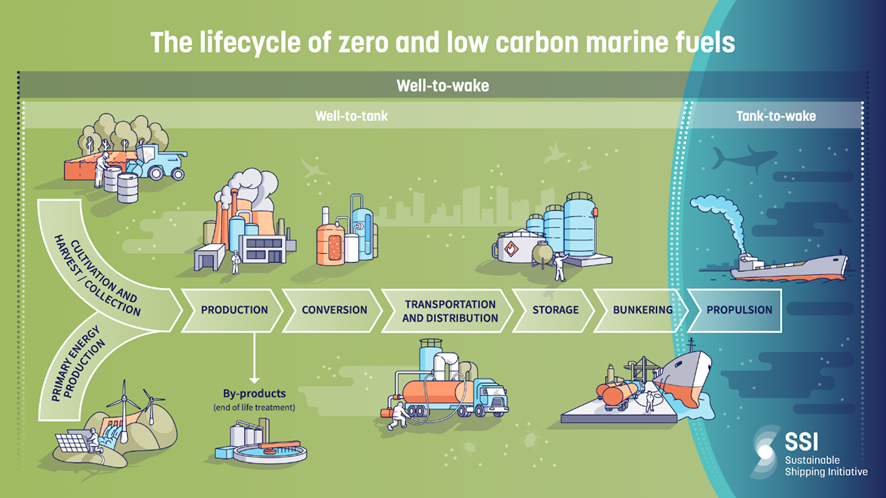

The regulation also specifies the methodology that must be followed to calculate a vessel’s emission intensity. This intensity is measured in greenhouse gas emissions per unit of energy (gCO₂e/MJ) and is calculated using a well-to-wake approach. In other words, the calculation takes into account not only the emissions generated from the use of energy on board the vessel, but also the emissions resulting from the extraction, cultivation, production, and transport of the fuel.

Illustration 5 WtW Methodology for Calculating GHG Emissions (SSI, 2021)

Penalties for Non-Compliance

We’ve already explained that vessels must reduce their GHG emissions compared to 2020 levels and how they must calculate their GHG intensity, but what happens if shipping companies fail to meet these emission reduction targets? The answer is simple: they will have to pay penalties.

Penalties under the FuelEU Maritime regulation are designed to encourage shipping companies to comply with the greenhouse gas (GHG) intensity requirements set by the regulation. In this context, the regulation establishes three types of penalties:

Penalty for Non-Compliance with GHG Intensity Targets

If the required annual emission reduction percentage is not met, a penalty must be paid. This penalty is directly linked to the amount of non-compliant energy used during that year, meaning that the greater the consumption of energy that does not meet the requirements, the higher the fine.

This penalty is calculated as the difference between the required GHG intensity (the set target) and the actual GHG intensity of a vessel, multiplied by the amount of energy used on the corresponding voyage. The energy used is determined by multiplying the mass of the fuel by its lower heating value (LHV) and the electricity supplied to the vessel.

The base penalty rate is €2,400 per tonne of Very Low Sulphur Fuel Oil (VLSFO) energy equivalent, which is approximately €58.50 per GJ of non-compliant energy.

Penalties for Non-Compliance with the RFNBO Quota

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, the Regulation sets consumption quotas for RFNBOs. So what happens if a vessel fails to meet the RFNBO quota? Simply put, it must pay a penalty. This is calculated as the difference between 2% of the total energy used on board and the total energy actually derived from RFNBOs, multiplied by the price difference between RFNBOs and the equivalent fossil fuel.

Penalties for Non-Compliance with OPS Requirements

Remember we mentioned that the Regulation requires vessels to use shore-side electricity while docked at ports? Well, ships that fail to meet the OPS requirements must pay a penalty equal to €1.5 multiplied by the total electrical power demand in port and the total number of non-compliance hours in port.

In addition, if a ship records a GEI intensity or RFNBO quota compliance deficit for two or more consecutive reporting periods, the penalty will progressively increase. This means vessels that repeatedly fail to meet targets will face increasingly significant sanctions, acting as a strong incentive for shipping companies to take corrective actions and reduce their emissions more efficiently.

As you can see, these penalties are designed to be sufficiently strict to ensure that shipping companies prioritize compliance with emissions regulations. In this way, a swift transition toward cleaner energy sources and more sustainable technologies is promoted, driving the maritime industry toward a greener and more sustainable future.

Now then, we’ve already discussed the objectives of the Regulation, its scope, and the penalties, but we haven’t yet addressed what shipping companies can do to comply with these requirements.

Below, we’ll look at some key strategies.

Strategies to Comply with FuelEU Maritime

It’s worth noting that there are different strategies that shipping companies can follow to reduce their GHG emission intensity and avoid paying these penalties. Want to know some of them? We’ll tell you!

Shipping companies can implement technologies such as wind-assisted propulsion or renewable energy on board to reduce their emissions.

Although, indeed, wind-assisted propulsion does not completely eliminate the need for fossil fuels, it helps reduce the amount of fuel required for a voyage. This directly lowers the ship’s carbon footprint. Additionally, the Regulation itself establishes a reward factor for vessels using this type of technology, meaning it also has an impact on GHG emissions calculations.

Moreover, the use of wind-assisted propulsion also involves a reward factor in the calculation of GHG emission intensity, which—depending on the technology used and its design—can be 1%, 3%, or 5%. This factor is calculated based on the design criteria of the technology, using the method developed by the IMO (International Maritime Organization).

Illustration 6 Vessel with wind-assisted propulsion using rigid sails (Exponav, n.d.)

The use of RFNBOs also receives a reward factor in the calculation of GHG intensity, which can be applied until 2033. This reward factor has a value of 2 when the fuel used is an RFNBO and is applied in the denominator of the GHG intensity calculation formula, providing an adjustment to the reported emissions.

Illustration 7 Stena Pro Patria vessel powered by methanol (PortalPortuario, 2023)

FuelEU Maritime also allows shipping companies to implement a “compliance pooling” mechanism between different vessels. Through this system, ships can reallocate their compliance balances among each other, enabling vessels with a negative compliance balance to offset it with the positive balance of others.

The main goal of pooling is to collectively meet the required GHG intensity targets, even if individual vessels fail to do so. This approach allows shipping companies to progressively adapt their fleets.

Illustration 8 Pooling mechanism between vessels (DNV, 2024)

In addition, the regulation allows the accumulation of compliance surpluses in cases where a ship exceeds the emissions reduction requirements. These surpluses can be carried over and applied to future reporting periods.

As we have seen, FuelEU Maritime marks a milestone in emissions regulation within the maritime sector, requiring shipping companies to make strategic decisions to adapt to the new framework. In doing so, shipowners will likely assess which strategy best aligns with their business model, considering aspects such as the cost of penalties, the use of biofuels, or the implementation of RFNBOs, which allow for the application of reward factors.

Below, we’ll examine a practical case study of a vessel and evaluate the impact of three different compliance strategies.

Case Study

To analyze the impact of the three previously mentioned strategies, let’s imagine a fictional ship like the one shown in the following image:

Illustration 9 Container Ship

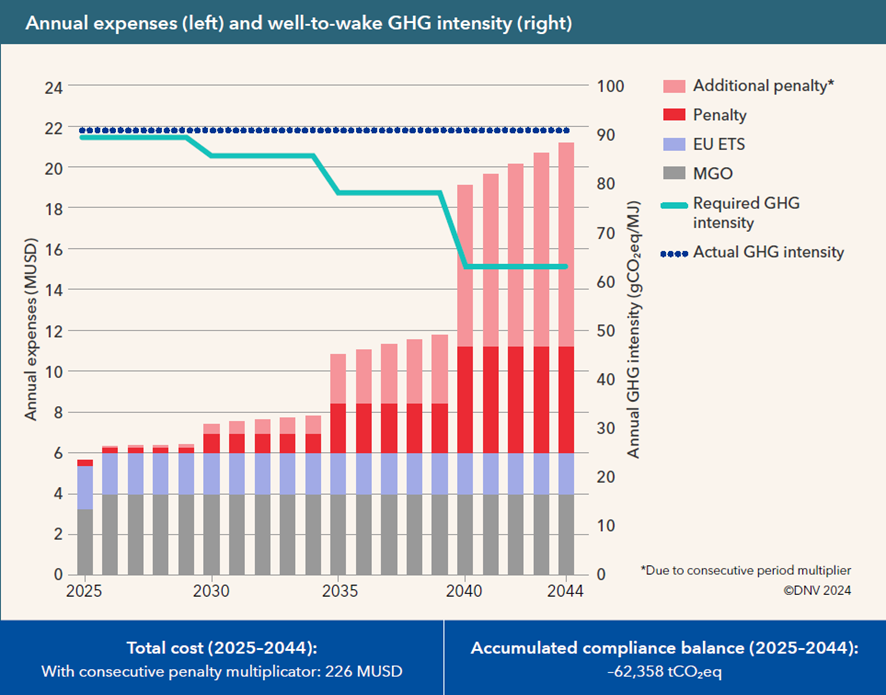

In the first strategy, the shipping company managing this vessel decides not to implement any corrective measures. As a result, the ship continues operating on fossil diesel MGO (Marine Gas Oil) throughout its useful life, from 2025 to 2044, and will be required to pay the penalties associated with non-compliance with the emission targets set by FuelEU Maritime.

Illustration 10 Strategy 1. Continue Using MGO and Pay FuelEU Maritime Penalties (DNV, 2024)

As shown, as the emission reduction targets increase, the penalties for non-compliance with greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction targets become more severe, with the cost of penalties surpassing the fuel price itself from 2040 onward.

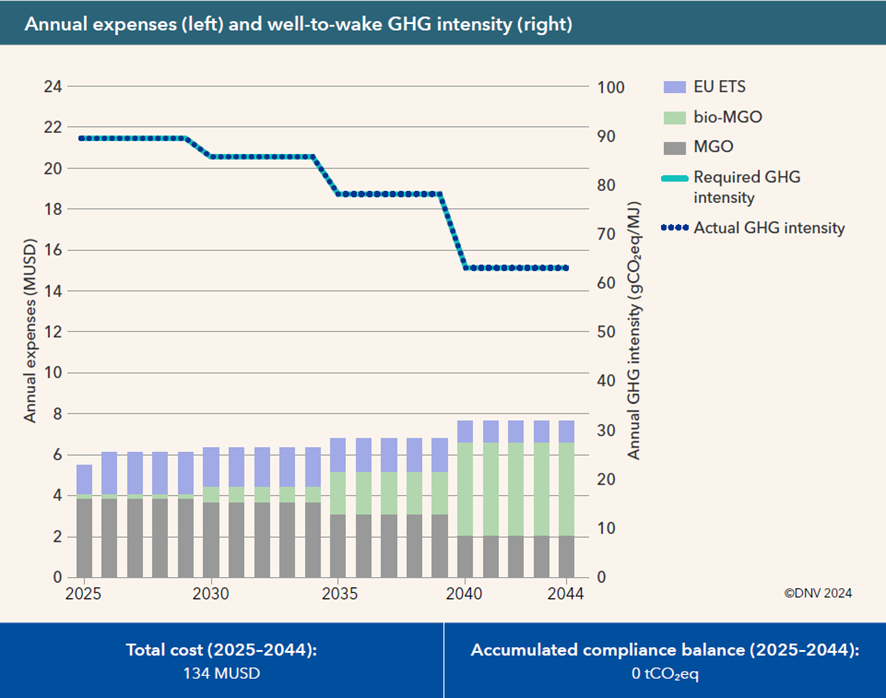

An alternative that this vessel could have considered is to continue using MGO from 2025 to 2044 while gradually incorporating the necessary amount of bio-MGO to meet the GHG emission reduction targets.

Illustration 11 Strategy 1.1. Continue Using MGO with the Necessary Amount of Bio-MGO to Avoid FuelEU Maritime Penalties (DNV, 2024)

As shown, the vessel does not incur penalties throughout its operational life, since it introduces the necessary amount of bio-MGO to maintain a compliance balance of zero in every year. It is evident that as the GHG emission reduction target increases, the share of bio-MGO in the fuel mix gradually rises.

Moreover, as the proportion of bio-MGO increases, EU ETS costs decrease while the fuel acquisition cost rises. Despite this, when compared to the previous strategy, it is significantly more economical to pay the higher fuel cost than to face penalties.

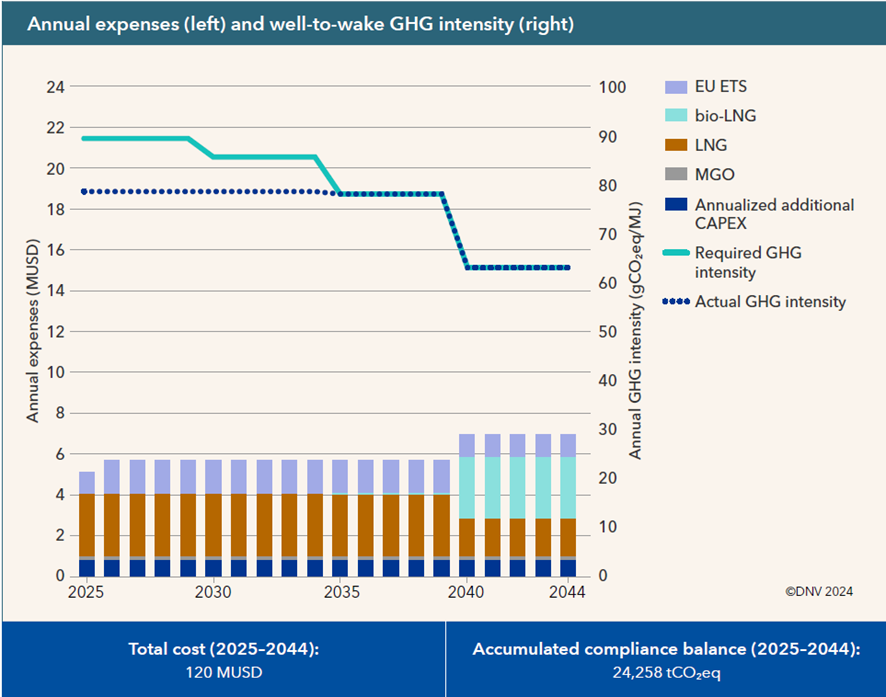

A third strategy could be for the vessel to operate using a blend of LNG (Liquefied Natural Gas) and bio-LNG, with MGO as pilot fuel (i.e., fuel used in small quantities to maintain or initiate combustion).

The amount of bio-LNG introduced by the vessel is precisely what is needed to meet the GHG reduction targets set by FuelEU Maritime.

Illustration 12 Strategy 2. Use LNG with the Necessary Amount of Bio-LNG to Avoid FuelEU Maritime Penalties (DNV, 2024)

As shown, from 2025 to 2034, the vessel’s GHG emission intensity is below the targets set by the regulation. This generates a surplus in the compliance balance, which could be used for other non-compliant vessels (pooling mechanism) or sold to generate additional revenue. This is mainly because LNG combustion emits fewer emissions than MGO.

Similarly to the previous strategy, as the share of biofuel increases, the associated fuel cost rises while the EU ETS-related costs decrease.

As can be seen from the last two graphs, this strategy is approximately €13 million cheaper than the bio-MGO strategy over the full period.

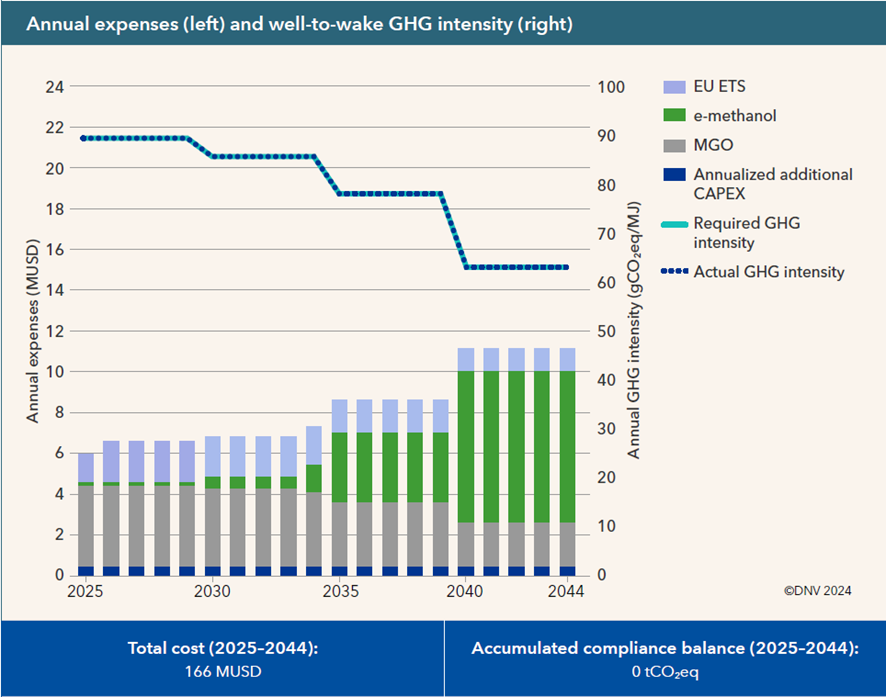

Finally, since the regulation allows reward factors for the use of RFNBOs, the vessel could consider using e-methanol as a viable strategy.

In this case, the vessel operates from 2025 to 2044 using a mix of MGO and gradually increases e-methanol consumption to maintain compliance with FuelEU Maritime.

Illustration 13 Strategy 3. Use MGO with the Necessary Amount of E-Methanol to Avoid FuelEU Maritime Penalties (DNV, 2024)

As shown—as with all strategies—as the emission reduction targets tighten, the amount of e-methanol required to comply and avoid penalties increases. During the 2025–2033 period, the RFNBO reward factor can be applied, allowing for a lower share of e-methanol in the fuel mix to meet FuelEU requirements. When comparing the years 2033 and 2034, the necessary amount of e-methanol increases significantly in 2034 to remain compliant.

Additionally, as the proportion of e-methanol increases, EU ETS-related costs decrease, but the cost of the fuel itself increases.

In overall costs, this strategy is approximately €42 million more expensive than the previous one. However, it is worth noting that starting on January 1, 2033, a separate RFNBO requirement may be introduced, which could add further benefits to this strategy.

Conclusions

As we have discussed, the FuelEU Maritime regulation presents both technical and economic challenges, while also creating opportunities for the development of sustainable fuels and new technologies.

The analysis of the various compliance strategies under the FuelEU Maritime regulation highlights the complexity and key decisions that shipping companies must make to align with the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reduction targets set by the regulation.

It has become clear that penalties will increase significantly over the years, even surpassing the cost of the fuel itself by 2040, making this strategy increasingly unviable in the long term.

The use of biofuels could even generate surplus compliance balances that may be used for other vessels through pooling or sold. The use of RFNBOs, such as e-methanol, allows for the application of reward factors, enabling compliance to be achieved with smaller amounts of fuel. However, despite their higher costs compared to biofuels, a potential requirement for RFNBOs starting in 2033 could tip the balance in favor of this strategy.

In summary, complying with the FuelEU Maritime regulations requires shipping companies to assess the available options. While paying penalties might seem feasible in the short term, strategies based on the use of biofuels and RFNBOs offer a more cost-effective approach that aligns with long-term climate goals.

At AtlantHy, we work daily to analyze profitable business models that support the adoption of RFNBOs by maritime companies. From methanol to ammonia, we help you sell your renewable fuels to businesses that, by regulation, must begin consuming these types of fuels.

References

Climatalk. (2021). Fit for 55: the Pathway to Salvation? Retrieved from https://climatalk.org/2021/07/24/fit-for-55/

DNV. (2024). FUELEU MARITIME.

DNV. (s.f.). FuelEU Maritime. Retrieved from https://www.dnv.com/maritime/insights/topics/fueleu-maritime/#:~:text=FuelEU%20Maritime%20is%20a%20regulation%20that%20will%20be,mix%20of%20international%20maritime%20transport%20within%20the%20EU.

European Union. (2023). Regulation (EU) 2023/1805 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 September 2023 on the use of renewable and low-carbon fuels in maritime transport and amending Directive 2009/16/EC.

European Union. (12 of 02 of 2023). Retrieved from Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/1184 of 10 February 2023 supplementing Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council by establishing a Union methodology setting out detailed rules for the production of renewable liquid a: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv%3AOJ.L_.2023.157.01.0011.01.ENG&toc=OJ%3AL%3A2023%3A157%3ATOC

Exponav. (s.f.). Propulsión asistida por el viento con velas rígidas. Retrieved from https://exponav.org/blog/puertos-y-buques/propulsion-asistida-por-el-viento-con-velas-rigidas/

PortalPortuario. (2023). Buque propulsado por metanol inicia ruta por Brasil con operaciones en Cattalini Terminais Marítimos. Retrieved from https://portalportuario.cl/buque-propulsado-por-metanol-inicia-ruta-por-brasil-con-operaciones-en-cattalini-terminais-maritimos/

ResourceWise. (July, 2020). EU Shipping Fuel Transition in Motion with Fuel-EU Maritime Agreement. Retrieved from https://www.resourcewise.com/environmental-blog/eu-shipping-fuel-transition-in-motion-with-fueleu-maritime-agreement

SES Hydrogen. (31st March 2023). AFIR: Alternative Fuel Infrastructure Regulation – the preliminary agreement would increase the number of hydrogen charging and refueling stations in Europe. Retrieved from https://seshydrogen.com/en/afir-alternative-fuel-infrastructure-regulation-the-preliminary-agreement-would-increase-the-number-of-hydrogen-charging-and-refueling-stations-in-europe/

SSI. (8 September 2021). Sustainable Shipping Initiative highlights need for sustainability of marine fuels to be considered in shipping’s decarbonisation. Retrieved from https://www.sustainableshipping.org/news/sustainable-shipping-initiative-highlights-need-for-sustainability-of-marine-fuels-to-be-considered-in-shippings-decarbonisation/

THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT. (2023). Renewable Energy Directive (2009/28/EC). Brussels.