Context

There’s a lot of discussion around the carbon footprint of fuels, especially when they are classified as renewable. This aspect is crucial for complying with environmental regulations that promote the use of sustainable fuels.

What does this mean in practice? Depending on the sector in question, the lower the carbon footprint of a fuel, the more attractive it becomes for end-use industries. However, this appeal is influenced by other key factors such as sale price and production costs. Only when a balance is struck between sustainability and economic viability can these fuels establish themselves as a true alternative to conventional market options.

One of the best examples of this trend is maritime transport, a sector already subject to the regulatory framework of the FuelEU Maritime legislation in Europe (European Commission, 2023). If you’re not yet familiar with this regulation, we recommend checking out our publication, FuelEU Maritime: Will ships in Europe consume RFNBOs?, where we discuss its implications in detail. In summary, this EU regulation requires a reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from ships through to 2050. To achieve this, it promotes the use of sustainable fuels, such as RFNBOs (Renewable Fuels of Non-Biological Origin) or low-carbon fuels, by means of a penalty system based on both the amount of energy consumed and the emissions intensity of the fuels used.

Illustration 1. Ecosystem for the production and use of hydrogen.

This is directly linked to the regulation that defines the permitted emissions intensity for synthetic fuels and RFNBOs. Based on these values, companies face proportional penalties: the higher the emissions intensity, the greater the penalty.

For this reason, companies are interested in minimizing penalties, as long as the cost of sustainable fuels makes it feasible. There is little point in imposing penalties if clean alternatives remain significantly more expensive. In such cases, many companies will opt for conventional fuels, as it is more profitable to accept the penalty than to adopt a lower-carbon solution.

In practice, most will choose the most economically favorable option. Only when the price and conditions of use of both types of fuel are comparable will the sustainability criterion be able to tip the balance.

In this context, the European Union has proposed a new delegated act that aims to establish a common methodology for calculating greenhouse gas emissions associated with low-carbon fuels, known as “Low-Carbon,” which we will examine below (European Commission, 2025).

The “Low-Carbon” Delegated Act

The recently adopted delegated act is presented as a key methodological tool to determine when a fuel can be classified as low-carbon (“Low-Carbon”), complementing Directive (EU) 2024/1788 on common rules for the internal markets of renewable gas, natural gas, and hydrogen (European Commission, 2024).

It is important to highlight that this regulation was initially scheduled for adoption by the end of 2024, according to the European Union’s original timeline. However, the process has been delayed, generating some uncertainty in the sector. As of today, the final resolution and its official publication are still pending, which will be crucial to understanding the final version of the legal text and its practical implications.

Its approach is similar to that of the delegated act that regulates the calculation of greenhouse gas emissions in RFNBOs, Regulation (EU) 2023/1185, as both instruments allow for the consistent definition, classification, and certification of different types of sustainable fuels in the European market (European Commission, 2023).

Who is affected by the “Low-Carbon” delegated act?

Given its synergy with the methodology used to determine the emissions of RFNBO fuels, this regulation directly impacts those fuels that, while exceeding the emission thresholds established for RFNBOs, still achieve significant reductions compared to conventional fuels.

As previously mentioned, this delegated act constitutes a legal document with implications both for the production of hydrogen and other low-carbon fuels, and for the behavior of potential buyers—such as the maritime sector—which faces regulatory obligations related to the carbon intensity of the fuels it uses.

Specifically, the calculation of emission reductions is based on a common reference value: 94 g CO₂/MJ. To be classified as low-carbon, a fuel must demonstrate a minimum reduction of 70% relative to this reference value.

In this context, it is essential to consider synergies with other European regulations, particularly the ETS Directive. The use of low-carbon fuels and RFNBOs not only contributes to decarbonization, but also allows companies to deduct from their reported emissions the amounts corresponding to the use of these fuels, thereby reducing their costs associated with the emissions trading system.

This strengthens the appeal of the regulation, as the implementation of a common methodology for emission calculation supports both the production and commercialization of these fuels in the European market.

This methodological approach aligns with the criteria established in the MRR (Monitoring and Reporting Regulation) and MRV (Monitoring, Reporting and Verification) regulations, allowing for coherent integration within the EU’s regulatory framework (European Commission, 2018) (European Commission, 2015).

Calculation methodology

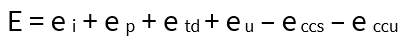

The emission factor of a low-carbon fuel is determined using the following formula, based on the sum of all emissions associated with the entire life cycle of the product.

In this way, it accounts for everything from the production of raw materials, transportation, and storage, to its final use at the end of its life, expressed in grams of CO₂ equivalent per MJ. Now, let’s analyze each component separately and understand what it means:

- e i: Refers to inputs, all emission contributions that occur during the production of the raw materials needed for the process.

- e p: Emissions associated with the actual production process of the fuel.

- e td: All transportation and storage of compounds throughout the value chain.

- e u: Emissions resulting from the final combustion of the fuel.

- e ccs: Emissions that are avoided from reaching the atmosphere and are permanently stored geologically.

- e ccu: Emissions that are avoided from reaching the atmosphere and are permanently stored in products.

In order to achieve a low-carbon fuel classification, it is crucial to consider the following points and aim either to reduce the contributing (positive) factors in the formula or increase the subtractive (negative) ones. Two key elements to focus on are:

The electricity used: Emissions from electricity that meet the requirements set out in the Renewable Energy Directive—previously discussed—for being classified as renewable can be considered zero-emission. In this context, one particularly interesting aspect is the flexibility offered by this Delegated Act: it allows for the accounting of electricity-related emissions based on four different methodologies:

- Average carbon footprint of the previous year in the bidding zone

- Hourly carbon footprint of the grid

- “Full load hours” method

- Carbon footprint of the energy source setting the marginal market price each hour

While it is true that once a calculation method is chosen, it must be maintained for 12 months, this flexibility allows us to make much better use of our electrolysis plants. At AtlantHy, we can help you make the most of these options based on the configuration of your projects.

Carbon capture (CO₂), which in some cases is used as a feedstock for the production of sustainable fuels, can—under certain criteria—be applied in the methodology as a factor that reduces the carbon footprint of the fuel. If the CO₂ is permanently captured in products or stored geologically, it directly reduces the final total emissions of the product.

Illustration 2. Carbon capture facility.

On the other hand, within the first component of the emission formula—input emissions—it is possible to deduct the amount of emissions that is incorporated into the chemical composition of the fuel and that would otherwise have been released into the atmosphere. This deduction is allowed provided the CO₂ comes from one of the following sources:

- The CO₂ has been captured from an activity listed in the Renewable Energy Directive, until January 1, 2036, extendable until January 1, 2041 in certain cases.

- The CO₂ has been captured directly from the air.

- The CO₂ originates from biofuels, bioliquids, or biomass fuels that meet the sustainability and greenhouse gas savings criteria set by the Renewable Energy Directive.

- The CO₂ comes from the combustion of RFNBOs or low-carbon fuels that comply with the greenhouse gas savings criteria established in the Renewable Energy Directive.

- The CO₂ has been captured from a geological CO₂ source and was previously released naturally.

- The CO₂ originates from inputs that meet the requirements as a carbon source for the production of recycled carbon fuels.

Thus, this mechanism allows, in certain cases, a significant reduction in the emissions associated with fuel combustion, even though this process inevitably generates emissions. The use of low-carbon fuels enables these emissions to be considered partially offset, thanks to the reduction they offer compared to conventional fuels.

What does this mean for fuel producers?

A key aspect is that this regulation includes a scheduled review in 2028, which creates some uncertainty for producers of renewable fuels, such as hydrogen—especially at a crucial time when competition among various sustainable fuels is high. For this reason, strict application and proper adjustment of the regulation are essential to ensure its effectiveness.

Moreover, the alignment between this regulation and the emissions calculation methodology for RFNBOs is vital to guarantee fair competition among the different types of low-carbon fuels. This is especially important in contexts where it is not possible to fully meet the RFNBO criteria, yet significant emissions reductions are still achieved and should be duly recognized.

Conclusions

This regulation aims to promote the production of sustainable fuels while establishing the necessary guidelines to classify a fuel as low-carbon. Such legal frameworks are essential to enable the effective implementation of other European regulations that set mandatory targets for the consumption of sustainable fuels as replacements for traditional fossil fuels.

As with the classification of RFNBOs, where the origin of the electricity plays a decisive role in the calculation of their carbon footprint, this regulation introduces criteria that allow for a more accurate assessment of the actual environmental impact of the final fuel. In this regard, it provides a more transparent and technical framework that distinguishes between energy solutions which, although they may not qualify as RFNBOs, still contribute significantly to emission reductions.

These regulations, pending final adoption and full regulatory development, are crucial for the technical and economic definition of projects. They help establish with greater certainty the environmental and regulatory viability of investments related to the production of hydrogen and other sustainable fuels, while also facilitating the analysis of these products’ competitive positioning in the market.

At AtlantHy, we support our clients with a detailed analysis of these regulations and their practical applicability. We assess their impact on the characteristics of the final product and its alignment within the European energy market, identifying risks, opportunities, and critical issues from the design phase through to commercialization.

References

European Commission. (2015). Reglamento (UE) 2015/757 del Parlamento Europeo y del Consejo, de 29 de abril de 2015, relativo al seguimiento, notificación y verificación de las emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero procedentes del transporte marítimo. Retrieved from http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2015/757/2025-01-01

European Commission. (2018). Reglamento de Ejecución (UE) 2018/2066 de la Comisión, de 19 de diciembre de 2018, sobre el seguimiento y la notificación de las emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero en aplicación de la Directiva 2003/87/CE del Parlamento Europeo y del Consejo. Retrieved from http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg_impl/2018/2066/2025-01-01

European Commission. (2023). Reglamento (UE) 2023/1805 del Parlamento Europeo y del Consejo de 13 de septiembre de 2023 relativo al uso de combustibles renovables y combustibles hipocarbónicos en el transporte marítimo. Retrieved from http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2023/1805/oj

European Commission. (2023). Reglamento Delegado (UE) 2023/1185 de la Comisión de 10 de febrero de 2023 estableciendo un umbral mínimo para la reducción de las emisiones de GEI aplicable a los combustibles de carbono reciclado. Retrieved from http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg_del/2023/1185/oj

European Commission. (2024). Directiva (UE) 2024/1788 del Parlamento Europeo y del Consejo, de 13 de junio de 2024, relativa a normas comunes para los mercados interiores del gas renovable, del gas natural y del hidrógeno. Retrieved from http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2024/1788/oj

European Commission. (2025). Metodología para determinar la reducción de las emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero (GEI) de los combustibles hipocarbónicos. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/have-your-say/initiatives/14303-Metodologia-para-determinar-la-reduccion-de-las-emisiones-de-gases-de-efecto-invernadero-GEI-de-los-combustibles-hipocarbonicos_es

Cundall. (2022). Reducing our personal carbon footprint (Cover image). Retrieved from https://www.cundall.com/ideas/blog/reducing-our-personal-carbon-footprint